George Seurat’s “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884” (completed in 1886) is an icon of 19th C painting and a centerpiece in the Art Institute of Chicago‘s collection.

I’ve always loved the Impressionist painters of that time (who doesn’t?), but frankly, the Post-Impressionist images of M. Seurat left me cold. Although he uses the same subjects as his contemporaries—middle-class French, especially Parisian, life—his formal, highly stylized figures and weirdly fascinating but tedious technique of building up tiny dots and dashes of paint (pointillism) lacks the spontaneity and life of the Impressionists. The Impressionists painted quickly, trying to capture an impression of a particular moment in front of them. Seurat worked for two years on “Grande Jatte”, including many preparatory studies. It is monumental in size: 10’ x 7’. Mounted on a central wall in one of the Art Institute’s Impressionist galleries, it seems visually quiet and aloof from the swirling life in the paintings around it.

And this is just as George Seurat intended.

He once said, “Some say they see poetry in my paintings; I see only science.”

Artists had been occupied with rendering things as “realistically” as possible since the Renaissance, creating illusions of “little windows” onto a particular scene. But with the invention of photography in the early 19th C, there were now machines that could do that—crude as they still were then. Artists began to explore other ways of seeing things. Along with scientists, they began to figure out how our eyes worked with the brain to create perceived images. Seurat was not so much concerned with what he was seeing (and therefore what we are seeing in his paintings) as he was with how we see it and what methods he needed to paint it.

“A Sunday on La Grande Jatte—1884” is not just the visual recording of a Sunday afternoon on La Grande Jatte Island in the Seine in Paris. Although it is that. It explores how we see that scene. Even if the painting isn’t as emotionally fun for me as an Impressionist’s impression of a similar scene, as a designer, the “mechanics” of how he did it are fascinating to me.

There’s only so much words can say about an object that is so intensely visual. The painting must be seen over and over for the eye and the brain to discover and absorb all that the artist is portraying. I’m going to touch on only one aspect of his exploration: How to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. Since the 15th C, Western artists had studied and mastered the geometry of perspective. In college, I took a yearlong class in perspective taught by a product engineer. Formal perspective is more science than art. The class was a grueling series of lessons trying to learn complex formulas and drawing precise angles, using T-squares and protractors and so on. My temperament is much more in step with art than science, I’m more with the Impressionists than Seurat. But the payoff to the class came on the last day when our engineer/instructor revealed, “Formal perspective is just a simulation. We really don’t see things this way. Everything I’ve taught you is horseshit.”

Seeing, it turns out, is more art than science.

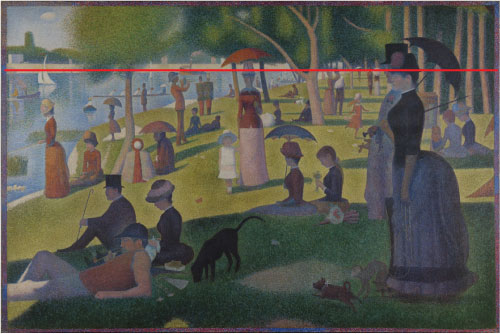

George Seurat knew this, of course. He was looking for other ways to create a spacial experience. He does use formal perspective. And then breaks its rules. In formal perspective, the artist sets up my (the viewer’s) point of view. First, he establishes the horizon line indicating my eye level. Seurat makes this overly obvious by making the horizon line the white wall stretching across the painting on the opposite bank of the river.

The horizon line establishes my eye level, not so coincidently, the eye level of the dominant, life-size couple on the left.

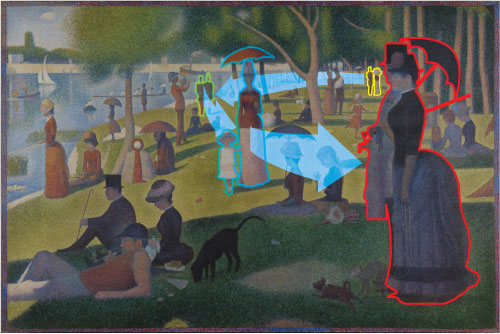

Reading left to right this line takes my eye very nearly into the eyes of the dominant couple, standing on the right. Painted life-size on this massive canvas, they seem to be directly in front of me. This establishes my pov on the right side of the canvas next to them. In effect, the artist is telling me where to stand in front of his painting. The line of the island’s riverbank leads my eye “back” in the illusionary space toward the horizon line and sets the vanishing point—that point on the horizon where all parallel lines running away from me converge. This point is in the tiny couple with their backs to me, directly in front of the dominant couple’s faces.

The vanishing point is located in the spot directly in front of where the artist would have me stand before his painting.

Depth perception dictates that similar objects will seem closer or farther away when one appears smaller than the other. That the left couple is so much smaller than the dominant set tells my mind there is a great distance, and therefore depth, between them.

But there’s more…

My mind links these two sets of couples because of their similarity to each other. In each a man walks arm-in-arm with a woman holding a parasol. They are the only such couples in the painting. Here, Seurat leaves the realm of classical perspective and moves into the perceptual psychology being studied at the time. (To be sure, artists have at least intuitively understood perceptual psychology since forever) These studies said that our brains tend to organize patterns and group similar things together. Recognizing the similarities in the two couples, my mind looks for other parallels. I find it in the similar silhouette of another couple in the painting: two soldiers standing somewhat to the left of center. They are similar, but different—they are facing forward. Now, noting similarities with difference, my mind moves my eye to another couple facing directly towards me, the woman with a parasol holding a child’s hand. Her parasol and the general direction of her gaze to the left link her back to the dominant woman on the right. The child, however, who is very nearly in the center of the painting, is looking directly into my eyes—the only such figure in the painting to do so. This further pulls me into the painting, reminding me of the life-size couple I’m standing next to. I’ve just completed a perceptual “walk” through the depths of the painting and back.

And the artist provides us with so much more. During my virtual perambulation, I pass “behind” and “between” other figures and trees that, because of their particular associations with still other figures and objects in the painting, further suggest the experience of three-dimensional space. Note the tree with branches reaching to the left. It’s the hub of my walk-around. The couple standing directly to its right emphasizes the tree’s importance. Note that her arms are lifted to the right mimicking the leftward lift of the tree’s branches. These are perceptual cues. My eyes are not just recording things for the brain to see, the brain is making associations that tell my eyes what to see and what to see next.

And again, there is so much more to see in the painting. George Seurat hasn’t recreated a view of La Grande Jatte I’d see had I been standing there on a particular afternoon in 1884. Instead, through his cool, dreamlike painting, he’s turned my perceptual eye inward, showing me how to experience it. The “window” Seurat creates is not so much out onto La Grande Jatte, as it is in through his mind.

One thought on “Sunday in the park with George..”