The Sources of Country Music, 1975, Thomas Hart Benton, 10’x6′, Country Music Hall of Fame, Nashville, TN

The old music cannot last much longer. I count it a great privilege to have heard it in the sad twang of mountain voices before it died.

—Thomas Hart Benton

Directly across from the wide entrance to the Rotunda of the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville is Thomas Hart Benton’s 10’ x 6’ painting, The Sources of Country Music. The artist was called out of retirement in 1973 at the promptings of singer Tex Ritter and commissioned for the commemorative painting. He was nearing completion in 1975 when he died of a heart attack at age 85.

Thomas Hart Benton was one of America’s most popular artists in the 1930s. Although as a young man he studied in New York and Paris, he returned to his Mid-western roots in Kansas City and along with artists such as Grant Woods developed the Regionalist style of American art. A self-proclaimed “enemy of modern art”, he stuck with his fluid sculptural representational depiction of populist American themes and characters even as art evolved through modernism and abstraction. (His most famous student was Jackson Pollack.)

Mr. Benton’s work is intentionally of a time and place. It’s dated-looking on purpose. He was also an amateur musician and a lover of folk and country music. It’s no accident that he was commissioned for the work just as country music was evolving from its various folk roots into mainstream pop. The painting is not only a memorial for the old music, but for Mr. Benton’s life and art, as well.

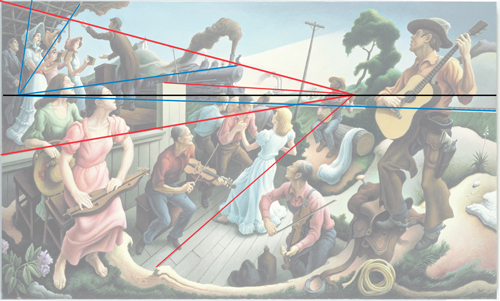

It is a wonderful painting! There are dozens of ways to technically dissect it, unwrap the structure and single out the notes and passages that make the picture, well, sing. It is visual music. Mr. Benton gives us a high horizon line and a vanishing point very near the left edge (just under the book-holding hand of the guy at that edge) and another about a third of the way in from the right edge (behind the banjo player’s upraised left hand). This has the effect of pushing everything to the left and creating a kind of loopy fisheye view where we see the leftmost and rightmost figures from below while we look downward on the more central figures. Only the upturned swale across the bottom keeps those figures from visually tumbling out on the floor.

The axis of various straight-lined objects lead the eye to the right balancing the leftward weight of the composition.

Although the crowd of figures on the left and the open space behind the cowboy on the right seem to weight the action towards the left, the axis of the various musical instruments and most of the other figures lean strongly rightward. The right-leaning angle of the central telephone pole continues through the dancing figure in the white dress across and near the center of the strong horizontal of the railroad track. This dramatizes the very active left/right, up/down, back/forth dynamic. And, like complex harmonies, the straight lines of the train track, phone pole, dance floor boards and window sill intermingle with the more fluid lines of the various characters and landscape. The viewer’s eye is kept continually dancing.

The fluid lines of landscape elements (green) and the more vertical lines of the figures (red) add visual harmony to the straight-line elements.

Much more can be said about Mr. Benton’s use of shape, tone and color, but I’ll leave that for you to discover.

It’s said that Thomas Hart Benton was unhappy with the train locomotive and was working on correcting it when he died (the painting is unsigned). The locomotive is the central character in this visual story. It is meant to literally depict the “engine of change” and refers to the steam engine in the folk song, John Henry. As it slashes across the painting near the horizon line, separating the gospel choir from its church home on the hill, almost all eyes seem suddenly turned toward it. It’s as if the engine’s shrill mechanical whistle is cutting through and overwhelming the raucous folk symphony. Leonardo said that every painter paints himself. I can’t help thinking that Thomas Hart Benton saw a very personal metaphor in that onrushing engine, as well.